Dr. Timothy Leary, Ph.D. (1920–1996), An extraordinary inner-space pioneer, outer-space advocate, ex-Harvard professor, psychologist, philosopher, explorer, teacher, optimist, humorist, author, and revolutionary avatar of the mind. Rightly called the Galileo of Consciousness, he went public with his observations of the mind made with psychedelic mindscopes and helped initiate a renaissance which is still only beginning to elaborate itself.

Full Name: Timothy Francis Leary

Born: 22-Oct-1920

Birthplace: Springfield, MA

Died: 31-May-1996

Location of death: Beverly Hills, CA

Cause of death: Cancer - Prostate

Remains: Cremated, Launched into space

Gender: Male

Ethnicity: White

Sexual orientation: Straight

Occupation: Activist

Military service: US Army

Level of fame: Icon

Executive summary: Tune in, turn on, drop out

Father: Timothy Leary, Sr.

Mother: Abigail Ferris

Daughter: Susan Leary Martino (with Marianne; d. 1990, murdered her boyfriend, suicide in jail)

Son: Jack (with Marianne)

Son: Zachary (with Barbara)

Wife: Marianne (m. 1944, d. 22-Oct-1955, suicide)

Wife: Nena von Schlebrügge (m. 1964, div.)

Wife: Rosemary Sarah Woodruff (m. 1967, div.)

Wife: Barbara Chase (m. 1978, div. 1992)

University Education:

Holy Cross College

West Point

AB, University of Alabama (1943)

MS, Washington State University (1946)

PhD, University of California at Berkeley (1950)

Only six words, "Turn on, Tune in, Drop out," it’s the debut pop-culture rap delivered by counterculture guru Dr. Timothy Leary, a man who gobbled over 5,000 doses of LSD in his lifetime and inspired President Richard M. Nixon to call him “the most dangerous man in America.” Leary was an intelligent, witty, unabashed hedonist who later in life became an internet enthusiast.

The government was indeed alarmed by how quickly teenagers flocked to Leary in the sixties and seventies. At the time, television and newspapers were filled with sensationalist tales of young people having horrible, deadly drug experiences. Politicians, police officials, and institutional psychiatrists all denounced LSD and marijuana as the most horrific threats ever confronted by the human race. When Leary sat before Ted Kennedy at a 1966 Senate hearing on LSD, he expressed disappointment at the media's complete absence of stories involving alcohol abuse, or the deaths resulting from Henry Ford’s faulty automobiles.

Timothy Leary was a professor at Harvard University when he began experimenting with psilocybin, acid, and other hallucinogens. His test subjects included prominent Bohemian luminaries like Thelonious Monk, Aldous Huxley, Allen Ginsberg, William S. Burroughs, and Jack Kerouac. After running low on beatniks, he switched to prison inmates, homeless people, and religious students. Leary argued publicly that hallucinogenic drugs could be used to treat personality disorders, but ultimately these beliefs got him booted from Harvard. His lifelong enthusiasm for tripping out would quickly overshadow his acclaim as one of America’s most notable psychologists. The inevitable goals of LSD sessions were (a) to discover and make love with God, (b) to discover and make love with yourself, and (c) to discover and make love with a woman.

In 1944, while training in Pennsylvania, he met a woman named Marianne. They got married, moved to sunny downtown Berkeley, and had two kids. Leary earned a doctorate in psychology and was appointed Director of Psychological Research at the Kaiser Foundation. He came to discover that one-third of patients who receive traditional psychotherapy get better, one-third get worse, and one-third stay exactly the same. He wondered if people wouldn’t be better off just getting high.

Meanwhile, Marianne had been suffering from post-partum depression, and she began to drink heavily. She and Leary fought with regularity. On his 35th birthday, he awoke to find Marianne in a closed garage with the car running. She was dead, the first in a series of family tragedies. Leary would later experience two more divorces and the suicide of his daughter.

In 1970, he declared himself a candidate for governor of California—but the campaign was cut short after he got arrested for drug possession. He and family members were pulled over by an arresting officer with a reputation for planting drugs on suspects. When Leary’s traveling companions were searched, the cops found hash and acid tabs. Leary pled no contest to possession of marijuana so authorities would go lighter on his family.

A trial in the most conservative county in California (and home of Richard M. Nixon) yielded a sentence of thirty years in prison for Dr. Leary, an offense normally warranting six months’ probation. During the appeal process, Leary was sent directly to jail. Astonishingly, he was given a prison psychological test largely based on his own research, and experts came to the conclusion that Leary appeared “healthy” enough to be transferred to a minimum security prison in San Luis Obispo.

Leary promptly escaped. He hoisted himself to the rooftop, climbed up a telephone pole, shimmied along a cable across the prison yard, and dropped over barbed wire to the highway below. He was smuggled out of the country with a fake ID. He was arrested several years later, extradited from Switzerland, and returned to a jail on U.S. soil. At this time, Leary decided he’d rather snitch on his accomplices than serve time. He helped finger the man who helped him escape from jail, recounted the escape plot, and implicated numerous others from Los Angeles and Seattle. Nothing led to a criminal arrest, and his sentence was reduced to three years.

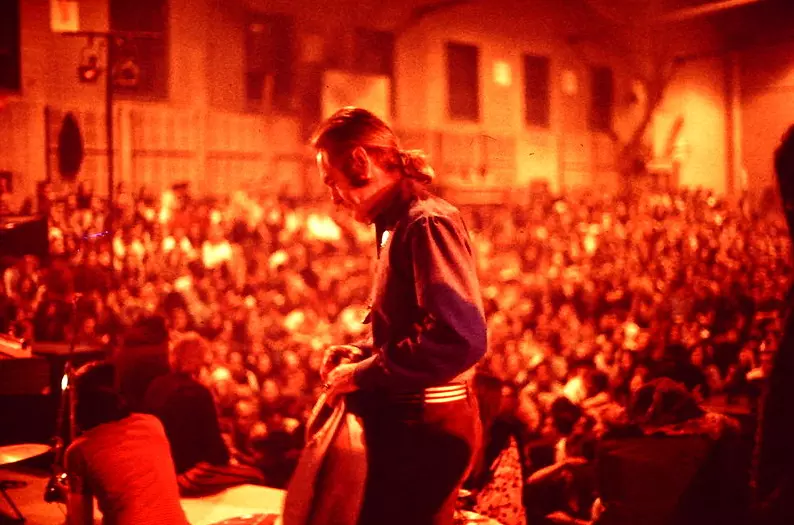

Upon release, Leary discovered his popularity had waned. He entered the lecture circuit as a self-proclaimed high priest of the psychedelic movement and continued to evangelize recreational drug use. Joining him at the podium was convicted Watergate felon G. Gordon Liddy, and together the two embarked upon a modest debating tour, appearing on college campuses from coast to coast. The reviews were mixed, and critics lamented the fact that Leary, a former Harvard professor, was now a nightclub comedian.

He was fifty-six years old with no home, no job, no credit, and dwindling credibility. He moved to Los Angeles and started socializing in Hollywood circles, a natural evolution for those attempting to alter perception. He believed that Hollywood and the Internet would be the LSD of the 90’s, empowering people on a massive scale.

His lectures became multimedia extravaganzas with live video and music, entitled “Just Say Know.” His books became graphic novels, focusing on the World Wide Web. He increased his daily diet to consist of 30 cigarettes, one marijuana biscuit, one bong hit, half a cup of coffee, and a great deal of nitrous oxide.

Dr. Leary died of inoperable prostate cancer, and he’d planned an elaborate death ritual for himself. He’d set up webcams where fans of his work could watch him commit suicide in real time. Instead, he died in his sleep, uttering the last words: “Why not.”

Later, his ashes were loaded into the same 9x12 inch canister containing the remains of Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry and blasted into space on the Pegasus Rocket.

In his 27 books and monographs, 250 articles, and more than 100 printed interviews published since the early 1950s, Leary has helped define the Humanistic Revolution which has had a huge impact on world culture. His books and papers as a psychologist in the 1950s helped launch the emerging "Humanistic Psychology" movement with an emphasis on interpersonal relationships, multilevel personality assessments, group therapy, body/mind interaction, and a libertarian redefinition of the doctor-patient relationship. Leary pioneered the controversial practice of group therapy believing that each group member needed to learn how to diagnose and direct their (Leary’s gender-unspecific term) own thinking and behavior rather than passively rely on "experts" (psychiatrists, psychotherapists, politicians, etc.). Leary’s research at Harvard with psychedelics led him to believe that the use of these substances under specific circumstances could help suspend and, in some cases, reprogram a variety of troublesome behaviors (including alcoholism and "personality" disorders).

His group’s most famous research project along these lines was the Concord State Reformatory Rehabilitation Study conducted in 1961 and 1962. The study showed a significant reduction of the recidivism rate of repeat offenders who took psilocybin with the guidance of Leary and company. A follow-up three years later showed a less impressive result regarding overall re-incarceration but a significant reduction regarding the rate of convictions due to new crimes.

In the late 1980s, Robert Dilts worked with Timothy Leary to extend his (Leary’s) ideas around "re-imprinting" into the world of NLP. From the work of Konrad Lorenz, Leary borrowed the idea of "imprinting" which demonstrates that some instances of learning take place during a critical period and usually result in permanent and irreversible behavior patterns. (Lorenz earned the Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine in 1973).

In the early 1970s, Leary took Lorenz’s idea of imprinting to a new level when he synthesized his eight-circuit model of consciousness from a variety of spiritual and psychological models. Leary suggested that human evolve through distinct stages in response to environmental stimuli imprinted at different critical developmental periods. The first four circuits (physical safety, emotional strength, intellectual prowess, sexual/social relations) were universal to humans at this time in history. Leary proposed that four additional stages (neuro-somatic, neuro-electric, neuro-genetic, neuro-atomic) may be triggered by novel environmental signals such as space exploration (whether outer space or cyberspace), genetic engineering, nanotechnology, and, of course, psychedelic drugs.

Leary’s work focused on the individual, he placed great value on fast feedback in small groups, especially among curious and intelligent people who knew how to have fun. When it came to having fun, he certainly seemed to practice what he preached. His ever-present smile and contagious enthusiasm cheered up his visitors while he was in prison during the mid-1970s after being declared "the most dangerous man in America" by then-president Nixon. Up to his final breath, Leary continued to surround himself with young people, especially artists, computer programmers, and others who he felt encouraged him to get smarter